To address the country’s worsening classroom shortage and ensure a future-ready education system, the Philippines must construct 7,000 new classrooms annually for the next 15 years. This was emphasized by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) in a recent discussion.

The recommendation was presented during a live podcast held on July 3 at Centro Escolar University. Titled “Classroom Shortages and Teacher Quality: Kaya Bang Mag-Level Up ng Polisiya?”, the event was hosted by Professor Jose Cris Sotto and featured insights from PIDS education experts, who pushed for long-term and systemic reforms to address the country’s decades-old classroom backlog.

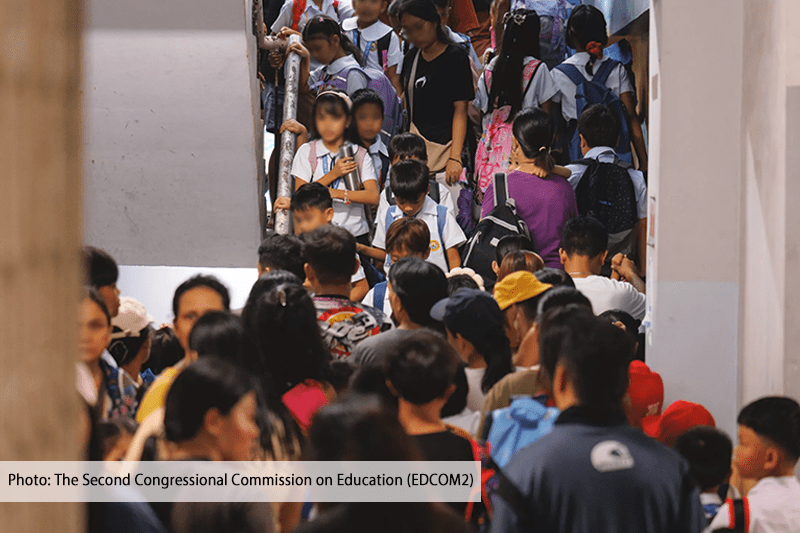

PIDS Senior Research Fellow Dr. Michael Ralph Abrigo, who authored the study “Low Fertility, Ageing Buildings, and School Congestion in the Philippines” for the Second Congressional Commission on Education (EDCOM 2), underscored the importance of collective action in solving the problem: “If education is something important to us, as a nation, we should be able to put our heads together to address this issue.”

The study notes that lower fertility rates and targeted infrastructure projects have reduced national congestion. Still, overcrowding remains severe in key areas such as Metro Manila, CALABARZON, Region XII, and BARMM.

In 2021, for example, over 90% of students in Northern Manila elementary schools were enrolled in classes with 50 or more pupils, Southern Manila recorded 76.8%, while Eastern Manila logged 60.1%. Nearby provinces, such as Rizal (66.0%) and Cavite (57.7%), showed similar strains.

The study projects a nationwide decline in school enrollment from 2040 to 2060 due to declining fertility.

“Per the PSA projections, if our Total Fertility Rate drops to around 1.7 by the 2050s, our population will start to decline… With fewer children entering school, we’ll need fewer classrooms and teachers,” Abrigo shared.

But this trend doesn’t apply evenly: regions like BARMM continue to see a rising school-age population, pushing local education systems beyond capacity.

Abrigo emphasized that infrastructure must be paired with bold and scalable reforms.

“DepEd is not in the business of constructing buildings. Their mission is improving education, and classrooms are just one part of that,” he said.

He cited public-private partnerships like education vouchers, which offer private school alternatives, to help ease public school congestion.

He also recommended flexible scheduling and shared space agreements for underutilized classrooms.

Abrigo also called for greater national support for under-resourced LGUs, particularly those unable to utilize their Special Education Funds (SEF).

Effective reform, he added, requires transparent, data-driven planning and coordinated infrastructure deployment among government agencies.

“Currently, classroom construction procedures are lengthened by phased budgeting, site verification, bidding, and hazard assessment processes,” he noted.

He recommended a forward-looking master plan, updated regularly to identify locations with impending demand, ensuring classrooms are built ahead of enrollment surges.

Abrigo also highlighted that these plans must consider local nuances—especially in disaster-prone regions—to reduce delays and wasted resources.

PIDS underscored that a shrinking youth population offers a chance to boost per-capita income—but only if the country invests heavily in education.

The so-called “demographic dividend” refers to the economic growth potential that arises when a country has more working-age people than dependents, like children or the elderly. But this opportunity only pays off if the workforce is healthy, educated, and productively employed.

“The demographic dividend isn’t automatic — we must invest in human capital through education, health, and employment to ensure our future workforce is ready,” said Abrigo.

This means not just increasing education budgets, but rethinking how the system is built and managed, Abrigo added.

“There should be a very strategic project management. It’s not just about the budget per se,” he said.

Leave a Reply